|

Joanna Southcott's Box |

|||

|

|

In 1927, Harry Price received at the National Laboratory a sealed wooden casket which the sender stated was the famous 'box' that once belonged to the prophetess Joanna Southcott. Harry Price described the Southcott affair in some detail in his Leaves from a Psychist's Case-Book, (Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1933). The complete contents of Chapter XVI 'Exploding the Southcott Myth' is presented below. p.289 PLAUTUS never made a truer remark than when he wrote, “What you do not expect happens more frequently than when you do" (Insperata accidunt magis sæpe quæ speres). I was minded of this when, on April 28th, 1927, I walked into the office of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research and was greeted by my secretary with the news, "Joanna Southcott's box has arrived!" I smilingly asked her what made her so facetious that morning and gently reminded her that it was not the first of April. But my smiles gave way to an expression of intense interest when she handed me a bulky metal-bound walnut coffer which had arrived with the following letter:

p.288

p.289

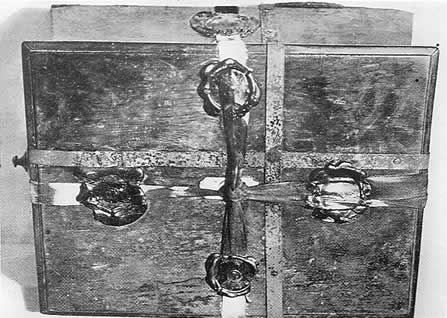

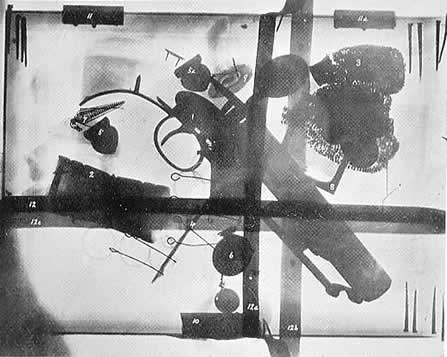

. . . . . . . . p.290 The letter bore the embossed heading of the Carlton Hotel, the manager of which I immediately 'phoned and ascertained that a gentleman of the name of F------ had been staying at the hotel and had the previous day departed for New York. The pedigree sent with the box bears the stamp of authenticity and I have checked up several of the statements contained in the letter. I will now attempt to describe the Southcott box which was sent to us. It measures 12½ inches long by 9½ inches wide and 6 inches high and weighs eleven pounds. It is a strongly built casket of walnut, much stained with age, with a heavy lid in which is sunk a mother-of-pearl plate bearing the engrave initials" I. S." (capital J's were written as I's in those days). Two rusty steel bands encircled the casket, which was further protected by strong silk tapes, much faded, secured in five places with large black seals bearing a fine young profile head of George III. The words,"GEORGIUS III D. G. BRITANNIARUM REX. FID. DEF.," can be discerned by collating the five seals. I made one curious discovery concerning the seals. I subjected them in turn to ultra-violet rays. Although all of, apparently, the same black wax, two of the seals react to the rays and give off a bluish-green fluorescence. The remaining three seals show no reaction. I think it is probable that Joanna ran short of one sort of wax after she had made three seals, and then used a different kind. Another theory is that long exposure to light may have caused two of the seals to undergo some chemical change: there are no signs that they have been tampered with. The illustration gives an excellent idea of the seals and fastenings of the box - which was locked, though no key was forwarded with it. Joanna Southcott was born of humble parentage at Gittisham, near Exeter, in A.D. 1750, and, when she grew up, became a domestic servant. She could read and write, and, having "got religion," she published, in 1801, a book of doggerel verse entitled Strange Effects of Faith. In this work she gave a short account of her life up to that time. She tells us that her first visitations were in 1792, by means of visions, and the "spirit of prophecy" came upon her. She claimed that these "prophecies" were the test of the genuineness of her mission, which was "to reveal the true meaning of the Bible, which had p.291 been closed up till her time, when God saw fit to reveal it through a woman" (i.e. herself). Gradually the "truth" dawned upon her that she was "Jesus Christ, in a woman's form," and thus it was the "second advent." This idea was soon after abandoned, when" Jesus Christ appeared to her, and announced that she was his chosen Bride"; and who afterwards became the alleged father of the "man-child" to whom, although a virgin, she was to give birth. Her writings attracted a good deal of attention all over England. A number of clergymen and others organised (in 1804) a "trial of her writings," and "twenty-four chosen men" (obviously a "packed" jury) declared that her writings were of divine origin. From this meeting can be dated the Southcott mania and the founding of scores of societies all over the country. Two of them exist to this day. Joanna claimed to be the "Bride of the Revelation," and, like many other brides, shortly announced that she was about to become a mother: in her case the mother of the new Messiah, or Shiloh, and her 144,000 followers were to greet his arrival. This special "creative power" - as she termed it - took place on February 11th, 1814, and in due time she appeared to show the usual signs of pregnancy. This new "immaculate conception" took place when Joanna was nearly sixty-five years old, and was hailed as the "sign and seal" of her special divine mission and set at rest any doubts as to her having been chosen of God to be the mother of the long-expected man-child spoken of in the Book of Revelation. Shiloh was due to arrive on October 19th, 1814, and, as the great day approached, Joanna's "144,000" went mad with excitement. They prepared an elaborate silver-mounted cradle (made by Seddons, a well-known London cabinetmaker) in the form of a miniature bedstead with a canopy surmounted by a dove. "Laced caps, bibs, robes, mantles, pap-boats, caudle-cups, and everything necessary for such an occasion," arrived by every mail coach, and the midwives of London fought for the honour of being responsible for the delivery of the august stranger. p.292 Of course the press made fun of the whole affair, and in the Morning Chronicle for October 18th, 1814, I find the following specimen of anti-Southcottian humour: "To morrow it appears is 'the great, the important, day, big with fate' of multitudes of miserable sinners, anxiously waiting to be white-washed through the merits of the forthcoming little Shiloh. The prophetess has, it seems, foretold the period of her accouchement to a minute - and the hour fixed upon is 12 o'clock - the very witching time of night. The happy news of the coming of Shiloh is to be announced to the Faithful by the sound of ten thousand Jew's-harps and penny trumpets!” The specified date came and passed, but the birth did not take place. The failure was accounted for by the "want of faith" on the part of the alleged faithful - just as a modern medium fails to deliver the goods because there are "skeptics” present in the circle!. Joanna's followers waited and waited, but no Shiloh came, though it became apparent that the prophetess was really ill. As a matter of fact, she died on December 27th, 1814. A postmortem examination resulted in the discovery that what had been taken for pregnancy was dropsy! She was buried January 2nd, 1815, in the "Mary-le-bone Upper Burying ground, near Kilburn." . . . . . . . . Joanna left a box; in fact, she must have left several boxes. But in the box was "something" that would save England in its hour of trial; some panacea that would lighten all our woes, rid us of the financial “depression," and knock four shillings off the Income Tax! At least, that is what was expected of it. With the box, which was to be opened only in a time of great national danger, were left very definite instructions. In the first place the box had to be opened in the presence of twenty-four bishops, who were commanded to comply with certain legal requirements which were not stated. Secondly, prior to the opening of the box, the twenty-four bishops were to prepare themselves by studying the collection of doggerel verse left by Joanna. Seven days were to be “devoted" in this way. There were also other "conditions." The public has always been fascinated with mysterious p.293 "boxes" : one has only to possess a box with a history and one immediately becomes a headliner. If it happens to be a locked box, so much the better. The human mind reacts in some subtle way to a mystery box, a fact which can perhaps be explained by our psychologists. Several famous boxes have created sensations, both in fact and fiction: the three caskets of The Merchant of Venice; Madame Humbert's locked - and empty - safe; the " Casket Letters" that played their part in sending Mary, Queen of Scots, to the scaffold for complicity in Darnley's assassination; Pandora's box; the Ark of the Covenant - all these "mystery boxes" have become classic, and I am quite certain that the reader would not now be perusing the history of Joanna Southcott if she had never possessed a famous "box." When the last of Joanna's boxes is opened, the bottom will fall out of the Southcottian movement. So the reader will appreciate my feelings when my secretary placed in my hands Joanna Southcott's famous "box." Though the prophetess left the strictest injunctions concerning the opening of her box, she made no mention of X-rays or psychometry: within fifteen minutes of the box coming into my possession I had decided to apply both. . . . . . . . . The arrival of Joanna's box provided a unique opportunity for testing the powers of those mediums who practise tactile clairvoyance or “psychometry," i.e. the alleged faculty of being able to "sense" the history of an object by merely touching it. Here was a sealed box which had not been opened for 113 years, and the contents of which were not recorded in any way: surely a brilliant chance for our mediums to exhibit their powers. I knew that some of them would commence guessing, as obviously, if the opening of the wonderful box was to be the means of "saving the nation," the panacea it contained must be in the form of the written or printed word. I was therefore prepared to receive statements concerning "documents," "manuscripts," "parchments," "books," and so forth. The mediums I invited to the test were Mrs. Florence Kingstone, Mrs. G. M. Laws, Mrs. Cannock, Mrs. Stahl Wright, Mrs. Eileen Garrett, Miss Stella C., Mrs. Cantlon, and Mr. p.294 Vout Peters. Dr. Arthur Lynch, the psychologist and former M.P., also tried his hand at psychometrising the box and a Mr. Francis Naish, M.A., wrote and informed me that by means of his pendule explorateur he had contacted at a distance, with the spirit of Joanna. Mrs. Kingstone clairvoyantly "saw" on old lady, a small stone cross, a "roll of parchment with writing which slopes to the left," piles of papers, a long sermon, the name Gerald, prophecies to do with religion and war, etc. Mrs. Laws clasped the box, and said: " I get a tremendous warmth; also a curious feeling of deadness." Mrs. Cannock held the box between her hands concentrated her mind on it for a few moments, and said: “There is a prophecy inside. A woman in a great white cap - a key - drawings or chart - a hard object - another box - something that is crumpled or rotted (dating to Biblical times) - writings - something made of bone - valuables, whether in money or effects - apparel. Mrs. Stahl Wright sensed "a little box " - a jewel - and the names "Edith," "Yates." Mrs. Eileen Garrett said: "Documents very badly written" - loose sheets of papers - manuscript containing prophecies and dates, strongly marked - something metal - bound book – portrait -a seal - scrolls, etc. The control ("Palma") of Miss Stella C. informed us (by means of calling out the letters of the alphabet) that the box contained coins, jewel, purse, ring, books, sheet of paper, beads, bag, seal, and the words “icey "and "loses." Mrs. Cantlon got "a piece of jagged marble " - small roll of paper tied with pink tape, and perhaps sealed - list of names and a short prayer - small white box – beads - quotations from the Bible - old-fasioned watch or compass, perhaps silver and rather dainty – “I am certain there are beads or stones" - "something long and dark" - "I get Jeremiah rather strongly; and Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John." Mr. Vout Peters went into a trance, and informed us that in the box were "three documents, one bound as a book" – scripts – curious drawings - something that is opaque - something long - lining of box is velvet - the name Jehovah - the year 18I2 - something to do with fabric. p.295 Dr. Arthur Lynch held the box for a few minutes, and said: "In my opinion, the box contains symbols and vestments, one manuscript of doctrine, and some directions to the faithful. Probably there is another box inside it which contains the most secret, sacred directions of all." I have now recorded most of what the psychometrists told us about their impressions concerning the contents of Joanna Southcott's box. Nearly every medium gave either "manuscripts," "writings," "drawings," or "books." Four mediums gave "another box" or a "smaller box"; two sensed “beads," and two said "seals." Speaking of seals, Joanna did a good trade in "sealing" the elect at anything from half a guinea to a guinea. Her "seal" comprises (many are still extant) a small quarto sheet of common writing-paper on which is drawn (usually with a compass) a circle. Within the circle, in six lines, are the following words : "The Sealed of the Lord - the Elect Precious - Man's Redemption to Inherit the Tree of Life - To be made Heirs of God and Joint Heirs with Jesus Christ." These papers were produced in quantities, by hand. About 14,000 of Joanna's followers were "sealed," but the trade fell off when one of the "elect," a woman named Mary Bateman, was hanged at York for murder! . . . . . . . . Within a very few hours after the psychometrists had done their best - or worst - with Joanna Southcott's box, I X-rayed it with the equipment belonging to the National Laboratory of Psychical Research, and, as The Times stated (May 6th, 1927), the proceedings were not without "excitement and interest." As a matter of fact, my Laboratory was besieged by all sorts of people (from scientists to pressmen), who wanted to be present at this very novel application of science to our research work. When Joanna left strict injunctions that her box was not to be opened except in the presence of twenty-four bishops, I am sure her prophetic soul never visualised the fact that a hundred years later the contents of her box could be examined without opening it. It has been stated that Joanna was an astute psychologist and, as someone remarked, she would have derived considerable satisfaction from the fact that p.296 the weapons of secular science - my Laboratory, the X-rays, and photography - would be used to gratify the curiosity of millions of people, 113 years after her death. . . . . . . . . I took five 15-inch by 12-inch negatives through the box, in various directions. The X-ray pictures came out exceedingly well, and we all had a good laugh at the articles we saw silhouetted in my radiographs. There was no mistaking what a few of the objects were, but some of the "shadows" puzzled us owing to all sorts of false visual judgments as to the real size, direction, and shape of the objects depicted. But we made out the following articles which formed part of the contents of the famous box: An old horse pistol (not cocked), date about 1814. Dice-box. Double-ended fob purse made of steel beads. Coins in the purse. A bone puzzle with rings. Books - one with metal clasps. A framed painting or miniature. Pair of gold inlaid, ear-rings. A cameo or worked pebble.

In addition we got the silhouettes or shadows of the lock of the box, the steel bands which surrounded it, and the handmade nails with which the portions of the box were fastened together. There were sensational stories going the round of the press that a number of wires were attached to the trigger of the pistol, so that when the box was opened the pistol would be discharged - and perhaps kill a bishop or two: Joanna’s post-mortem revenge! . . . . . . . . Having X-rayed the box, there was little more to do except open it - with or without the assistance of the twenty-four bishops. p.297 According to the various versions of the Joanna Southcott “story," ten, seventeen, or twenty-four bishops were necessary for the formal opening of her "mystery box," but it was generally conceded that four-and-twenty (like the blackbirds of the nursery rhyme) was the requisite number - which was taken from the twenty-four elders mentioned in the Book of Revelation. No one seemed to know exactly why, when, or where the bishops should open the box. We were told that it must be opened only in time of "dire distress," "grave national danger," "to avert our country's downfall," "to save the nation," etc. Well, it was easy for us to make the excuse that the nation wanted saving from something - and we had a wide choice of evils (from politicians to jazz) that we wanted to be rid of. I was not particularly concerned whether it was, or was not, necessary for a certain number of bishops to be present at the opening of the box. But the pedigree which we received with the casket clearly states that Joanna left the most solemn injunctions that her box should be opened only in the presence of a full bench of bishops. This being the case, I decided that I would at least make an effort to induce the bishops to attend the formal opening of the box. To this end the following letter was sent to three archbishops and eighty bishops:

Most of the bishops replied to us, and the answers to our circular letter were amusing, sarcastic - or even rude! The great majority of the bishops wanted to be present if their duties permitted, or if they happened to be in London. The Archbishop of Canterbury sent me a charming letter which is of historical interest. It was addressed from Lambeth Palace, and is dated May 14th, 1927. He informed me that his correspondence about Joanne Southcott's box or boxes extended over many years and was very voluminous. He told me that his views concerning the opening agreed with my own and that it was desirable to avoid any mystery in the matter, and that the box should be opened by "serious people in the presence of such group of persons as are interested in the matter." His Grace strongly deprecated the giving of any weight to the proposal, which he regarded as "partly profane and party comic," that twenty-four bishops, representing the twenty-four elders in the Book of Revelation, should sit round while the box was being opened: this was one of Joanna's stipulations. His Grace approved of the box being opened "as speedily as may be," but thought that immediately we opened the box, a rival box would at once be found. The Archbishop of York saw "no reason why the box should not be opened." The Bishop of London replied that he would try to be present. p.299 The Bishop of Derby hoped that we could get a quorum for the opening, in order "to lay to rest the Joanna Southcott legend." The Bishop of Kensington was sarcastic, and remarked that any hoax derived its point from involving a number of seriously occupied persons, in distinguished positions, sitting round in circumstances of great solemnity. He concluded his letter by saying that he did not wish to be a party to provide amusement for a public who would like nothing better than to see a company of bishops the victims of such a hoax - even if the "hoax" was arranged 100 years previously. The Bishop of Carlisle replied that he would be present if the Archbishop of Canterbury "should be satisfied as to the propriety of bishops being present at the opening of the box." The Bishop of Lincoln strongly advised me to open the box "with or without the presence of bishops." The Bishop of Liverpool wrote: " I join you in hoping that the Southcott myth will be exploded." The Bishop of Chichester said that he would be glad if the Southcott myth could be exploded and would be willing to be present, if in London. And replies, similar to those recorded above, were received from many other bishops. But the reader can hardly fail to notice that bishops - like doctors - disagree. But it was apparent that many of the bishops wished to be present if they could get to London, or if the Archbishop of Canterbury gave them permission. A point raised by some of the bishops was whether our box was the box. But no one knows which is the box containing the great secret. Joanna left several, and I can imagine her saying to herself: "It's a fine day, I think I'll seal a box! " . . . . . . . . The public opening of Joanna's box took place at the Hoare Memorial Hall, Church House, Westminster, on July l1th, 1927, at 8 p.m. Prior to the opening I inserted an advertisement in The Times, to the effect that anyone possessing a Southcott "mystery box" could have it opened at the same time, free of charge! We received no replies. The projected ceremony aroused extraordinary interest p.300 among the public and the large hall was crowded. Followers of the two existing Southcott societies were present and they created some disturbance: they declared that the opening of our box was "sacrilege." I replied that I was determined to knock the bottom out of the Southcott myth and that the box would be opened. I also received a number of threatening and abusive letters from the fanatics who still maintained that there was something in the box which would make a noise in the world - even if it was only the sudden discharge of Joanna' pistol! The bishops let us down badly. Whether they were too busy or afraid of the pistol going off, or had not obtained permission from the Archbishop of Canterbury, I do not know. But only Dr. J. E. Hine, Bishop of Grantham, was present. The Bishop of Crediton was represented by his son, the Rev. Trefusis. We prepared a pleasant evening for our "opening." I gave a lantern address on Joanna's activities, and Professor A. M. Low - who presided - made some humorous remarks on mass psychology and the madness of crowds, with special reference to "the particular form of lunacy known as the Southcott movement." (Hisses from Joanna's supporters.) Professor Low then announced that the box would be opened, and a wave of excitement passed over the hall: the Great Moment had arrived! I picked up a heavy pair of metal shears and proceeded to cut the two steel bands which encircled the box. [Plate XXVII.] After I had cut the bands and the faded silk tapes, I prised open the lid with a jemmy and asked the Bishop of Grantham to remove the contents, one by one, at the same time as I gave a description of the articles to the excited audience below me. I was not aware of any particular sensation as I opened the box or helped to remove the contents, but one paper said I opened the box "gingerly"; another paper declared I removed the contents "with trembling fingers"; while a third reporter remarked "on the growing scorn " on my face as I realised what the objects were. All these accounts were inaccurate: I opened the box unconcernedly as if it had been a box of chocolates, and as for being "scornful" of the contents, I at once realised that they were of real antiquarian interest and of no little intrinsic value. p.301 The audience, like those on the platform, could not help being struck by the way in which the X-ray photographs had given us clues to the objects found in the box. All our deductions were correct. The pamphlets, books, etc., indicated by shadows, were not clearly discernable in my radiographs, but the solid objects were all as I anticipated. It is impossible to give a complete list of every object (there were fifty-six articles) in the box, but among the books I will mention The Surprises of Love, Exemplified in the Romance of a Day, or An Adventure in Greenwich Park Last Easter j the Romance of an Evening or Who Would Have Thought It? (London, 1765) with annotations by Joanna; Rider's British Merlin (London, 17 I 5); Calendier de la Cour (Paris, 1773); Ovid's Metamorphoses (London, 1794), etc. Rather a worldly collection for a religious ecstatic! There was a lottery ticket for 1796, and a piece of paper "printed on the River Thames, Feb. 3rd. 1814." In the, green silk double-ended fob purse, covered with cut steel beads, were a great number of silver and copper coins and tokens, ranging from a William and Mary 2d. Maundy piece to a ½d. mail-coach token. Some of these coins are rare. Among the miscellaneous objects were the horse pistol (rusty and quite innocuous!), a miniature case, turned ivory dice-cup, a bone puzzle, a woman's embroidered night-cap, pair of tortoise-shell and inlaid gold drop ear-rings, and a set of brass money weights. If someone had put the collection before me and, without telling me their history, I would have hazarded a guess that they belonged to some old roué or gambler! In the current (14th) edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica it is stated that the box I opened "contained nothing of interest." This is untrue. The date of opening is given as 1928 - this is also untrue. It must be admitted that Joanna left a most amazing and heterogeneous collection for the benefit of posterity, and it is a matter of speculation as to what her intention was. It has been suggested that the prophetess sealed them as one seals up a collection of articles under a foundation-stone: typical of her generation and of interest to succeeding ones. Or the objects were perhaps intended to be symbolic. One thing is quite certain, there is not a shadow of doubt that the box and its contents belonged to Joanna Southcott. p.302 It is interesting to compare the psychometric impressions of the mediums with the known contents of the box. As a matter of fact, some of the psychics were very successful - even at guessing! Stella C. mentioned several articles which were eventually found in the box. The two words "icey" and " loses" were quite unintelligible to us at the time, but "icey " might refer to the slip of paper printed on the ice when the Thames was frozen over in 1814; and "loses" might be the word by means of which " Palma" tried to convey to us that the owner of the lottery ticket which the box contained had lost. It was a losing ticket, or it would have been given up. . . . . . . . . I hope we have discharged out trust satisfactorily as to the opening of the box. We did our best to meet the wishes of Joanna, the subsequent guardians of the box, and the Devonshire gentleman who sent it to us. If the box contained nothing of an epoch-making nature, that is not our fault, but Joanna's. The London Times, in a long leading article (July 13th, 1927), emphasises that "the National Laboratory of Psychical Research acted throughout with complete openness and nice discretion in its treatment of the queer charge entrusted to it ...." "There seems to be no doubt," The Times continues, "that this box, or ark, and its contents had been the property of Joanna Southcott. The former owners believed that it was the right box, given away by her on her death-bed with strict injunctions about its opening. Did she also give away the other boxes under like conditions? Mystification, due to a loss of hold on truth or fact rather than to a deliberate intention to deceive, is common to such enthusiasts. They attempt to continue by any means the assertion of themselves as set above the rest of mankind. Joanna Southcott, claiming to be a heavenly bride in a sense very different from that applicable to every nun -indeed, to every good woman - is to be the mother of a Messiah. Nowadays we call it megalomania, and think it a pitiable affliction. But more pitiable, because indicative of a feebler vitality and courage, is the commoner affliction of credulity on which this megalomania is nourished. Our age prides itself on being a rational and scientific age; yet even p.303 to-day Joanna Southcott's box is by no means the only will-o-the-wisp upon which eyes are fixed in the hope that it will lead to safety. Her known writings are sufficient proof that nothing she had to say could possibly save the country, or even add a spark to the enlightenment which mankind already has. Yet belief in her will continue until the last of the boxes has yielded up its secret." I quite agree with The Times leader writer, but doubt very much if the box in the possession of the Blockley Southcottians will ever again be opened. (It was opened in 1840 and found to contain only manuscripts.) No bishop would waste seven days studying Joanna's published writings (part of the "simple conditions" laid down by the Southcottians). And, what is more, the Southcottians do not want their box opened, in spite of their parrot cry to the bishops to "send for it." The Southcottian movement of to-day would not last a month unless they had at least one sealed box to whet the curiosity of their followers and, I must admit, the public at large. No box, no mystery; no mystery, no "movement"! The Southcottians without their" box" would have as much "go" in them as a motor-car without its engine. It would be unthinkable. But they will never get another bishop to touch a Joanna box with the proverbial pitchfork. But that does not affect the present handful of modern disciples of Joanna. Although these latterday Southcottians admit that the box I opened was one of the real ones-or even the real one-there are others, and they will keep the movement going. Nor are Joanna's followers at all abashed by the fact that the box I opened contained nothing to "save the world." If the much-advertised panacea is not in the National Laboratory box, then it will be found in another box! These Southcottians have the sort of faith that moves mountains: a faith eclipsed only by their stupendous credulity. That Joanna was a genius of sorts is proved by the fact that nearly 120 years after her death she is still compelling us to expend our time and energy in debating the point whether this " Bride of the Lamb" was a much-maligned saint or a very astute sinner; an inspired prophetess or a cunning charlatan. I think that Joanna was a genius in obtaining publicity - a publicity which she can still command. I suppose the Southcott myth will never really be p.304 dead until all of Joanna's boxes are opened and their contents known. If the formula for regenerating mankind is not found in anyone of them, then, perhaps, the memory of Joanna and her box will be cherished only by those historians whose business it is to entertain us with accounts of mass delusions and the madness of crowds.

PLATE XXV

PLATE XXVII

|

||

The Base Room . Biography . Timeline . Gallery . Profiles . Séance Room . Famous Cases . Borley Rectory . Books By Price . Writings By Price . Books About Price . Bibliography . Links . Subscribe . About This Site All original text, photographs & graphics used throughout this website are © copyright 2004-2005 by Paul G. Adams. All other material reproduced here is the copyright of the respective authors. |