|

Biography |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Many years after his death, the flamboyant figure of Harry Price, psychical researcher and entrepreneur, continues to excite controversy. Renée Haynes gives a new assessment of the varied career of this extraordinary man.

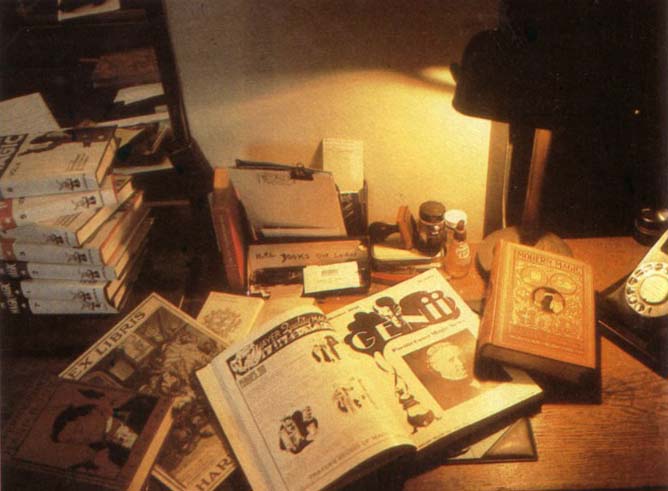

HARRY PRICE IS FAMOUS for his work in bringing psychical research to the attention of the public. He was a man of a warm heart, a clear head, a keen nose for news - but his work was bedeviled by the fact that he also had much ambition, no academic conscience, and a passion for the limelight. In his autobiography Search for Truth he recorded that in his youth he had wanted to become a writer; and he retained throughout his many books and articles a gift for producing lively and very readable material - too lively, too readable for some of his critics, who felt that he preferred a telling phrase to minute scientific accuracy. Among his ambitions were to contribute to Encyclopaedia Britannica (which his father, in Harry's childhood, bought in monthly installments); to be in Who's Who; to collect the largest library of books on magic in existence, and to be offered an honorary doctorate by a university. He succeeded in must of these aims. He did contribute to Encyclopaedia Britannica, he appeared in Who's Who (though some of the statements he made in his entry were queried after his death). And he certainly amassed a huge library. After enquiring as an incredulous eight-year-old just how an entertainer had got two pigeons out of an empty hat, he was given a 'conjuring manual', the first item in what was to become a collection devoted to conjuring tricks, Spiritualist writings and objective psychical research. As far as his ambition to be awarded a degree honoris causa was concerned, a suggestion was indeed made that he should be awarded an honorary doctorate, by the University of Bonn, in consideration of his offer to cooperate in setting up a parapsychology department there in conjunction with Professor Hans Bender. Price withdrew in 1937, however, when he thought that the University of London might fund a similar venture - and the doctorate was not awarded. According to Price's own account, his interest in psychical research started early. As a boy, he claimed, he spent much of his spare time wandering round street markets and fairs looking at fortune tellers, hypnotists, quack doctors, and conjurers, and closely observing their methods; and on occasion he visited local séances. He also began to write plays, to cultivate an interest in archaeology and to collect Roman coins. On leaving school he joined classes in electrical engineering, and later evening classes in mechanical engineering, chemistry and photography.He wanted to become an engineer, but by the time of his marriage in 1908 he was, like his father before him, employed as a commercial traveler - a job that demands aptitudes for making new contacts, getting on with businessmen and sizing up situations quickly. It is interesting to compare Price's experience with his remarks in Leaves from a Psychist's Case-Book (1933) on 'what constitutes an ideal psychical researcher'. To 'familiarity with psychic literature of all countries' he adds 'an acquaintance with foreign languages, a knowledge of chemistry, biology, physics, mechanics, medicine' - and conjuring. This formidable polymath must also have 'a charming personality, the hide of a rhinoceros, a clear conscience, a sense of humour, and exceptional tact'. Price himself certainly had a number of these qualifications - although many people would jib at describing his conscience in the matter of professional ethics in psychical research as clear. In fairness to him, it is only right to say that Price's undoubted talents lay elsewhere than in academic research. Energetic, ambitious, itching to make his mark in a world he had experienced as highly competitive, Price was in all probability unaware of the code of honour that many of his fellow psychical researchers took for granted professionally. Price's contrasting assumptions, his methods, and his undisguised love of publicity jarred upon them.

Sensitivity may make a man conscious that something is wrong, but it does not necessarilv show what that something is. Price interpreted the chill disapproval of his colleagues in psychical research as social snobbery; this, understandably, aroused a deep resentment in him, and may well have led to the fantasies about his own ancient lineage and professional background that he peddled as fact and that undoubtedly damaged his reputation for integrity. Music hall turns Price's marriage seems to have improved his finances - his wife had a small private income - and enabled him to spend more time on his overriding interest. During the years before the First World War he investigated both 'vaudeville mediums' appearing as music hall artists and small-time practitioners who gave private séances. He discovered that they relied on a fine assortment of tricks. One performer whose methods Price exposed insisted on using, wherever he went, his own armchair - which, he claimed, was 'saturated with magnetism'. Sitting in it in the dark, Price discovered, the 'psychic' could unlock a panel in the back against which he was leaning, and gain access to a collection of hairpieces, masks, rolls of butter muslin with coat-hangers to put them on, a collapsible dummy, and other props.

A heart ailment that troubled him all his life prevented Price being called up for military service. Nevertheless, his knowledge of mechanical engineering meant that he was put in charge of a small munitions factory. He still had time enough left over from his activities there to investigate some 20 allegedly haunted houses, but with little definite result.At the beginning of the war Price had determined to found a laboratory for testing professional 'psychics'. This resolve was reinforced during the course of the war by the sight of people attempting to peddle séances to the bereaved, and to the relatives and friends meeting trains carrying soldiers returning home on leave at Victoria station; the soldiers and their relatives were also offered all manner of amulets, talismans and 'letters of immunity' against death. It was no doubt his lasting disgust at this exploitation of human misery and anxiety that prompted him, in the 1930s, to draft with a barrister friend a 'Psychic Practitioners (Regulation) Bill'. This aimed to repeal the Witchcraft Act of 1735, amend the Vagrancy Act of 1824, under which mediums and fortune tellers were liable to prosecution, and examine, register and control professional psychics in such a way as to make fraud impossible. This, a Private Member's Bill, was dropped at the outbreak of the Second World War.

Photographic exposure After 1919, Price continued his project of founding his national laboratory, and in 1920 he joined the Society for Psychical Research. Here he co-operated from time to time in a number of investigations with various distinguished members, among them Mrs K.M. Goldney and Dr E.J. Dingwall, an experienced - and relentless - research officer. His exposure of the 'spirit photographer' William Hope, whom he caught substituting a prepared photographic plate for the marked one he had given him, appeared in the society's journal in 1922, and caused considerable controversy. In 1923, according to his own account, he met on a train a quiet, shy, young woman later known as Stella C.; she asked if she might borrow the copy of Light that he had been reading, as she had had odd experiences of her own, and would like to know more about them. She turned out to be a gifted psychic, and it looks as if his subsequent work with her was what made Price take an increasing interest in establishing fact, rather than concentrate on exposing fraud. Like others who collaborated with him in this case, he became certain that the phenomena she produced were genuinely paranormal, including the curious unexplained sensations of cold reported independently at séances by Sir Julian Huxley and by Dr E. B. Strauss of St Bartholomew's Hospital.

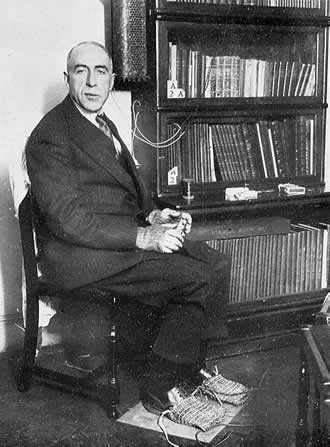

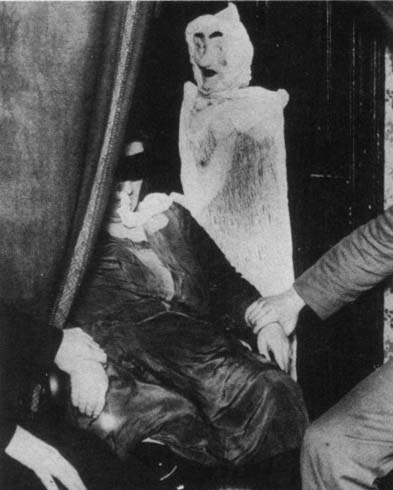

As a result of Price's report on Stella C., he was appointed in 1925 London-based Foreign Research Officer to the American Society for Psychical Research, and went on working for it until 1931 when, as the result of an upheaval over the integrity of a famous medium, who used the pseudonym of 'Margery', the society was temporarily split and the post abolished. 'Margery' was later found to have passed off as 'spirit fingerprints' those of her living dentist. During his tenure of the post, however, Price had used his opportunities to the full: he had travelled extensively, making contact with psychical researchers in Austria, France, Germany, Poland and elsewhere, observing their methods and discussing their results.His own National Laboratory of Psychical Research, which he had set up in a small way in 1923, flourished, and by 1926 boasted a lively council that included distinguished foreign members, and a large laboratory with advanced scientific equipment - including apparatus for producing x-rays, infra-red light, flashlight cameras, thermographs, dictaphones, microphones, and so on. There was also an electrical chair for use in 'dark' séances, a device that automatically recorded periods when a medium was not sitting on it and could therefore be engaged in producing fraudulent phenomena.The laboratory moved more than once. In 1930 its lease at the premises of the London Spiritualist Alliance ended and, after the Society for Psychical Research had refused to concern itself with the venture, Price took over new premises. Among the many alleged psychics investigated here was the 17-stone (110 kilogram) 'materialising medium' Helen Duncan, who produced spirit forms revealed by flashlight photographs to consist largely of cheesecloth; the weave, the selvedge and various tears and dirt marks were plain to see. Rubber gloves and a safety pin were also found; the rubber gloves presumably became the 'hands' of the materialised spirits, while the safety pin held their floating 'robes' together. Helen Duncan was thoroughly searched before she put on her one-piece black sateen séance garment, and retired to the equally thoroughly inspected cabinet in which she produced her marvels. The observers, of whom two were medical men, finally concluded that she swallowed and regurgitated the 'phantoms' - possibly, they speculated, from a secondary stomach. Price recorded that on being asked one night to agree to an examination by x-ray, the large lady rushed off, opened the front door and fled screaming down the street, hotly pursued by three professors, two doctors, and various other sitters.

In the public eye Price's inability to refuse any challenge, however ridiculous, often led him into absurd situations. On one occasion, in 1932, he set off for the Harz mountains with Professor Joad to take part - in connection with the Goethe Centenary celebrations - in a folklore ritual in which a white billy-goat, after magical ceremonies, was supposed to turn into a handsome young man. He also could not resist the claims on his attention of Gef the 'talking mongoose', alleged to haunt an isolated farmhouse in the Isle of Man. This 'beast' sang, screamed, threw things about, read the papers, laughed, and sent investigators a tuft of hair (identical with that of the family collie) and some remarkable paw prints in plasticine; but on the morning on which Price was due to visit the farm, the creature deserted it, and did not return until the researcher had departed. Nevertheless, Price was aware of the publicity value of the affair and conducted a thorough investigation into a case that most psychical researchers dismissed out of hand. The Price of Fame - The second of Renée Haynes's articles on Price and his work from The Unexplained magazine. |

|||||||||||||||||

| The Base Room . Biography . Timeline . Gallery . Profiles . Séance Room . Famous Cases . Borley Rectory . Books By Price . Writings By Price . Books About Price . Bibliography . Links . Subscribe . About This Site All original text, photographs & graphics used throughout this website are © copyright 2004-2006 by Paul G. Adams. All other material reproduced here is the copyright of the respective authors. |